Ever since I read Heathen Chinese‘s post about Boxers & Saints by Gene Luen Yang, I’ve been waiting for our library to make them available. I loved his American Born Chinese and I anticipate loving these books even more.

But I’m saving them as a reward for whenever it is I finish a statement of purpose draft for a grant due in mid March. Since I’m stalled on that piece and barred from reading the books I so dearly want to read, instead let’s look at a fictional account of the Boxer Uprising, written by a British woman in 1902 called Out in China! I read it sometime last fall so that you’ll never have to.

The Boxers, as the English called the members of the Righteous Harmony Society (義和團), struck fear into the hearts of foreigners in northern China from 1899 to 1901. A sectarian religious group centered on martial arts and spirit possession, it appealed to mostly young men dispossessed by the calamities of the 19th century. Its rhetoric included calling for the expulsion of all foreign and Christian influences in China and its members believed that the spirits they called upon to help them do battle fought through them, alongside them, and also made them invulnerable to bullets. The crumbling Qing government eventually supported the rebels and imperial forces joined them in laying siege to the foreign legation of Beijing. In mid 1900, an alliance of foreign powers marched inland, defeated the Chinese forces, occupied and then sacked much of Beijing.

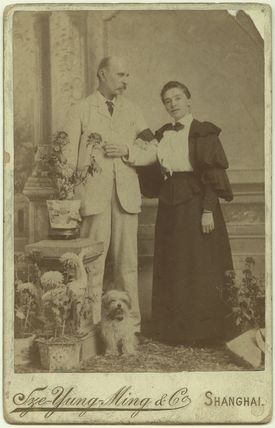

In the midst of all this mess, let me introduce you to Mrs. Archibald Little. Before she married in 1886, at the advanced age of 41, she wrote under the name Alicia Ellen Neve Bewicke.

After her first book, published when she was 23, she wrote 9 more novels of manners and society with strong female protagonists searching for their purposes in life. She evidently found hers when she moved to China with Archibald, a successful businessman, and wrote ten more volumes of fiction and nonfiction about her new home. Books like Intimate China, Round about My Peking Garden, and Land of the Blue Gown introduce China – its curious oddities and its awesome attractions – to readers back at home.

Some of the few non-missionary 19th century books about China I’ve read, she paints a less dire picture of the state of Chinese culture and religion. Not that they couldn’t still use a good dose of British civilization, but she argues that the missionaries are going about their work all wrong when they don’t take into account and honor native traditions. She was also a vigorous campaigner against footbinding and seriously concerned about the place of women in society – both Chinese and Western. Highly opinionated about everyone around her, not just the Chinese, and unafraid to express her views, she’s a fascinating figure. And, as it turns out, a mediocre novelist.

In 1878, the British magazine The Spectator, condescendingly described Miss Bewicke as, “one of the best of the second-rate novelists.” The Spectator then reviewed Out in China! in 1902. The review goes:

The primary object of this book may be said to be that of a political pamphlet. People in England do not think enough about China, or, if they think, probably think wrong. This is really what Mrs. Archibald Little has to say; but then, the ordinary reader of fiction has to be considered. A bride goes out to Mr. Lindsay in China, but unhappily the wrong one; it should have been the aunt; it is the niece. Hence troubles which it is not difficult to imagine. There are some good things in the story; but this toujours pedrix of unlawful love, served up everywhere and anywhere, is really beyond all bearing. So, at least, it seems to us; but multitudes of people must like it, for there is little else in novels, or on the state.

Yes, still condescending.

Here’s how the comedy of errors intersects with the Boxers:

Willfully ignorant of the ongoing strife in the hills around the bay where the British live isolated on an island, a group of men and women, including the wrong bride, set off for a lovely picnic. Inevitably, they are attacked by Boxers. Half of the party escapes, hiding in the hills, while the rest are brutally murdered and their mutilated corpses hung from trees to be found by the vigilante rescue party formed the next day.

In a chapter called, “What! Another Picnic!” that gets more macabre and chilling each time I review it, Mrs. Kitley, whose sister was one of the victims, is barred from seeing the body. The men of the rescue party intentionally distract her by getting her to serve them a picnic with the makeshift supplies they brought along. Then, they encourage her to drink plenty of whisky. As her husband begins to break the news, the party’s doctor gives her a dose of some kind of tranquilizer to drink.

“Shall I not even move and go to her?” she asked.

“No, no!” [her husband] shrieked rather than said, and put himself in front of her.

“No, no!” rose as in a chorus from the other men.

“Do not move,” from the doctor.

By the end of the novel, she has wholly lost her mind out of grief for her sister.

Nearly everyone else in the party attacked that day, in one way or another, goes a little insane. And, tragically, the young woman who accidentally came to China in place of her aunt dies of heatstroke while waiting for rescue, but not before admitting her love for her husband’s best friend moments before she expires.

The final chapter begins thusly:

“Of course things quieted down as they always hitherto had done in China, and nothing particular came of it all, though there were some rather fierce newspaper articles written at the time…”

It’s unclear what the greatest tragedy is here – the first marriage to the wrong Winifred, her subsequent death, the insanity of Mrs. Kitley, the ignorance of the foreigners in China, or the indifference of the government back home. It’s a romance novel stitched Frankenstein’s-monster-like with some fierce newspaper articles that Little herself may have wished to write.

The point of all this, I suppose, is that had Great Britain cared more about the fate of its business people and consular staff, it would have protected them from the start. Alicia Little attempts to bring problems that feel so far away – out in China! – near enough to British readers’ hearts to make them sympathetic. But to whom? And to what end?

It’s unsatisfying fiction that mystifies in all the wrong ways.

One thought on “Out in China with Mrs. Archibald Little”