The following entry comes from a thread I posted on Twitter today that I’d been mulling over for about a week. If you’d prefer to read it over there, click here.

I know I sometimes sound cavalier about the horrors depicted in the texts and images I work with from nineteenth century China, especially related to the Taiping War (1850-1864), but the truth is that it is really difficult some days. This is one of those days, but I also think that my best work happens when I am empathetic instead of distant.

Awake early before my paper presentation this morning deciding just how many woodblock print illustrations of death and destruction to show my audience as we kick off day 2 of this lovely conference. pic.twitter.com/HxBRE59Frf

— K. Alexander 亞天恩 (@thian_un) October 20, 2018

Back in October, I ran out of time to show images from Yu Zhi’s (余治) Jiangnan tielei tu 江南鐵淚圖 (A Man of Iron’s Tears for Jiangnan) but, in a way, I’m glad I did. Until last week I’d only seen these in facsimile reprint, but now I’ve received an original via ILL (🙀), and the images are so detailed that I can’t help but mourn an 150-year-old war. Below are a few of the forty-two full-page illustrations that accompany Yu’s poetry, commentary, and various appendices (depending on which edition you get your hands on).

In the first illustration, the Taiping soldiers attack while the locals scatter, leaving behind some, in pieces, and their homes on fire. Through the book, it feels as if you follow the desperate journeys of the refugees through the wasteland of war, from one danger to another.

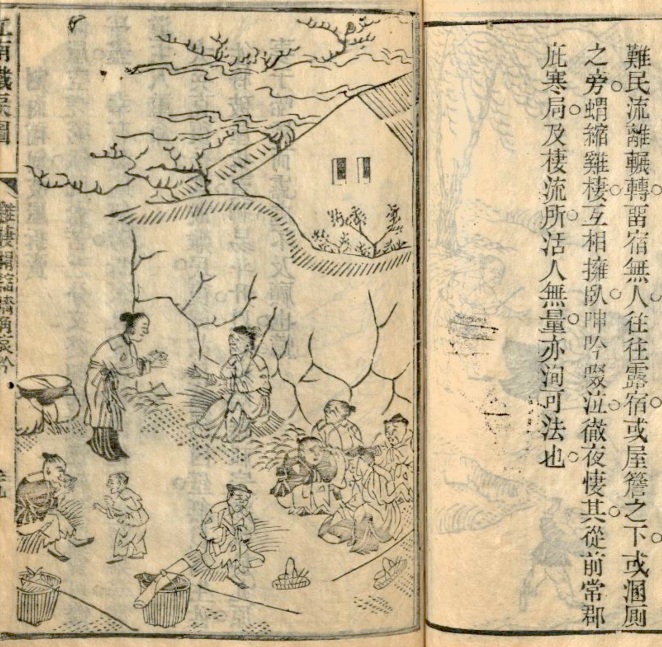

In this, which I should carefully rescan to account for bleedthrough, though no Taiping soldiers pursue the refugees now, still they wander from right to the left of the page, and when the weakest lack the strength to carry on, what can the stronger few do but press on towards safety? So many, Yu notes, fall along the way.

Now the Taiping forces are back, and the refugees are stymied by a river that cannot be crossed except with boats, and the single boat pictured is too small for all those waiting on the shore.

Here’s that text and image I teared up over the first time I read it: What happens to women and children separated from their families and wandering in search of food or shelter? It looks as if they’ve found some food, but the path at the bottom left beckons them onward…

Now is as good a time as any to point out that such families and children, if fleeing into the US in 2018, might be separated from each other with no clear promise of reunion or be turned away at the border by volleys of teargas. Refugees need asylum.

So my heart of iron mourns too because this text, from far off in time and space, seems all too familiar. What can we do today?

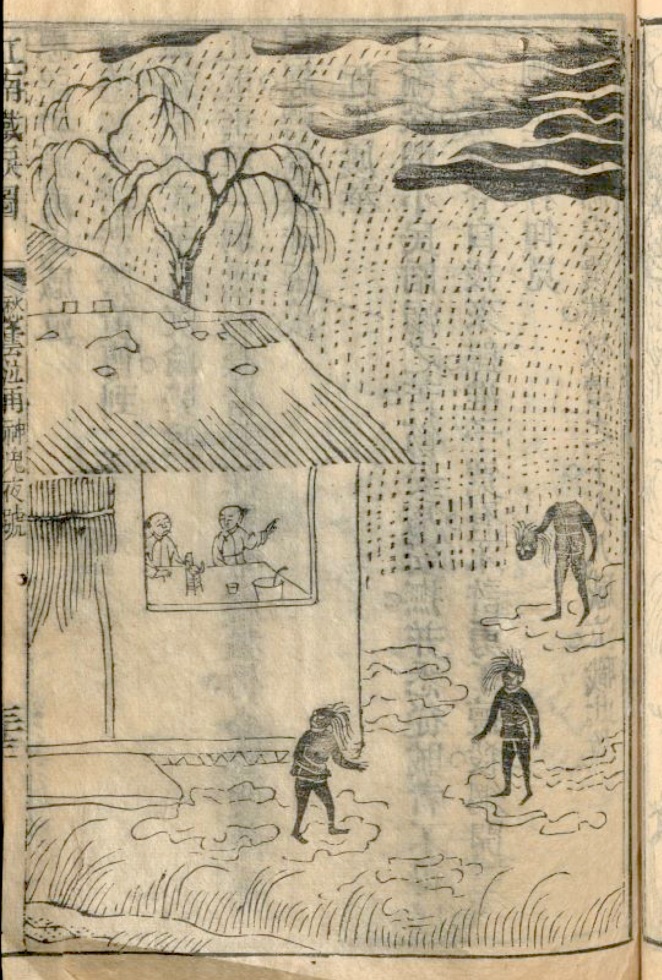

To cap off his descriptions of the human cost of war, Yu wrote that the cold nights are filled with ghosts of the friendless, and the anonymous illustrator at 蘇州得見齋 drew this to chilling perfection.

An appendix which follows this text says,

“在明眼人看來家中堆積的錢米他並不是堆積的錢米也。直是堆積着無數餓死人的皮骨血肉也 To the perceptive, the rice and money piled up in your homes are not really piles of rice and grain. They are only the flesh and bones of innumerable peopole who starved to death, piled into a great mound.”

I didn’t know how much I would need Yu Zhi’s words when I started working with his writings five or so years ago. It’s from spending time contemplating the faces in these prints that I understand the earnestness imbuing Yu Zhi’s bureaucratic apparatus of hope.

“須知道世間財物。原是天公物。要他流通救世。You must know that all the wealth in the world is actually Heavenly public property, and it must circulate in order to save the world.”

What are we supposed to do with our plenty?

Some places I’ve donated (although not nearly enough of my plenty, I’m sure) include HIAS, the Texas Civil Rights Project, and Refugee One.

How do you share?

By the way, after that illustration of the countryside haunted by all who died because no one would help, Yu shifts his focus to what good might happen if his readers all find a way to help. Restoration is possible.

In the final image, readers are asked to contemplate the spectacle of the crowd drawn to see morality plays onstage, something Yu hoped would make people so good that war would never come again.

No more unending roads in the bottom left corner lead refugees off to places where they will still not find the safety they seek.

Instead, a little child drags his mother towards a peddler with treats, because a world restored means sweetness for all.

From a fellow Rice-Graduate, comes the Financial insight that the “Velocity of Money” must increase for prosperity. So part of the problem is the wealth and rice is in “piles”! Buying & Selling, vs. Hoarding decrease ‘publick’ misery. -David Upp

[In Bulacan Province… we spent 14 interminable hours in wearying attempts to crawl cross massive Manila’s sprawl] ________________________________